What Is It Really Like to Be a Teacher?

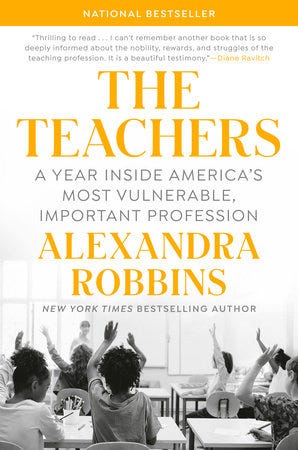

The Teachers: A Year Inside America's Most Vulnerable, Important Profession by Alexandra Robbins

I’m standing in front of my class of 3rd graders, and my room is bulging with 40 students. They are screaming and throwing pencils, and my efforts to quiet them are just met with laughter. “You suck!” one student yells.

On the first day of the college semester, I realize that I am teaching a course in advanced statistics that I’ve never taught before. I have no lesson prepped, no materials, just 100 students in a large lecture hall staring at me blankly. I may or may not be wearing pants.

Both of these situations happened to me — at least in what I refer to as my “teacher-out-of-control dreams.” This term was coined in conversations with my brother Mike (high school anatomy/physiology teacher) and my sister-in-law Melanie (2nd grade teacher), and it refers to a particular type of nightmare that haunts each of us before a new school year begins.

Between the three of us we have exactly 100 years of teaching experience, and yet these dreams still crop up every fall.

In The Teachers: A Year Inside America’s Most Vulnerable, Important Profession, author Alexandra Robbins shares the experience of a 4th grade teacher who calls this particular type of dream a schoolmare.

“… schoolmares,” school-based nightmares featuring students, coworkers, or the school building, typically starring Rebecca standing in front of the class inexplicably lacking lesson plans.” (p. 101)

This is just one of many anecdotes from the book that rang true for me as a teacher of students in preK through graduate school over the last 38 years. The Teachers not only highlights the rewards of teaching but the struggles, and its stories shine a harsh light on the lack of support that many teachers experience. I wish every teacher, parent, administrator, and policy maker would cancel all appointments and read this book today.

The book’s basics

In The Teachers, veteran journalist Robbins follows the lives of three educators throughout one school year: “Rebecca” is an east coast 4th grade teacher, “Penny” is a 6th grade math teacher in the south, and “Miguel” is a middle school special education teacher in the western United States. (The author changed or omitted some of the teachers’ identifying details in the book.)

The book’s chapters are organized by month from August through June. In this way, the reader can follow the trajectory of each teacher’s year, from anticipation of the first day of school — to questioning one’s life choices midyear — to finding some resolution by the time the last day of school rolls around.

In addition to these three teachers’ stories, Robbins includes various quotes and experiences drawn from hundreds of interviews with teachers around the country. All together, these voices communicate the realities of being a teacher in America today. And it often isn’t pretty.

Out of the mouths of parents, administrators, and other sharpshooters

At the start of each chapter, Robbins presents a few horrifying examples of interactions between teachers and parents or administrators:

“I am here today to inform you that my daughter will not be working from your syllabus. I have prepared another syllabus with anticipated works and anticipated dates that my daughter will create for your AP Art class.” (p. 144)

“A science department chair to a Maryland high school teacher who was in tears because of overwork: ‘Stress is good for you.’” (p. 208)

“My daughter is not to be crossed. I taught her how to punch.” (p. 266)

Why did I look forward to these chapter openings with an odd sort of relish? Clearly I don’t like seeing teachers being mistreated. Perhaps it’s because these interactions, not unbelievable or surprising to anyone who has spent even a short time in teaching, provide a sense that we teachers are not alone.

Self-compassion expert Kristin Neff lists “recognition of the common human experience” as one of three core components of self-compassion. If as a teacher I can see that others are experiencing similar situations, I can resist taking things personally. Of course, that does nothing to stop the abuse. However, it prevents me from inflicting further damage by circling the psychological wagons and shooting inward.

I have a trove of my own horror stories, mostly from my time as an elementary school teacher. Like the time a parent came to a conference with cocaine just above his upper lip, or when I saw a parent beat her child with a bull whip in the front office, or how my principal was arrested for soliciting prostitutes during the lunch hour . . .

In addition to these short snippets, the monthly trials of the three teachers paint a picture of toxic school cultures and cliques, struggles to advocate for students and schools in need, the difficulty of balancing teaching with a personal life, violence against teachers, unsupportive parents, insufficient resources, unrealistic demands, and, perhaps most of all, feeling overwhelmed by the many responsibilities and expectations placed on teachers.

And then there are the joys

And yet, teachers show up day after day to do the job for which they were hired (although their numbers are dwindling and will likely continue to do so without system-wide intervention). Robbins deftly illustrates special moments experienced by each of the three teachers. Rebecca reveled in inside jokes with her class, like when she misheard a student proposing a subject for her poem. (“Jesus” and “Cheez-Its” do have a similar ring!) Miguel successfully advocated against the closing of his school, and Penny helped a special education student with a lifelong aversion to math not only pass the state math test but to proclaim, “I like math!” (I won’t go into this story any further, but I was crying hard at the end of it.)

I recall in my elementary teaching years regaling my husband and young children at the dinner table each night with a “funny teaching story of the day.” Like the time when my police officer husband came to deliver sand to my kindergarten classroom on his day off, and I teased the children beforehand that, “The sandman is coming!” One particular student, a transplant from New York, became increasingly fearful all morning. Relieved when he figured out it was only “Mr. Duggan,” he ran up to his mother at the end of the day exclaiming, “It wasn’t the sandman; it was only her fah-thuh!”

Is teacher burnout a myth?

“What if the premise of teacher burnout is a myth, a convenient fiction that blames teachers for not being able to cope rather than faulting school systems that set both teachers and students up to fail?” (p. 223)

The scholarly portion of my career focused on studying teacher mental health. So when I encountered the section entitled, “‘Classroom Contagion’: The Myth of Teacher Burnout,” my hackles were momentarily raised. But as I read on, I was impressed by the case presented by Robbins that situational factors such as “insufficient classroom resources and administrative support; not enough teaching assistants; lack of decision-making input; unpaid overtime; too much high-stakes testing; and the lack of other disciplinary and other policy enforcement” are intense drivers of teacher dissatisfaction.

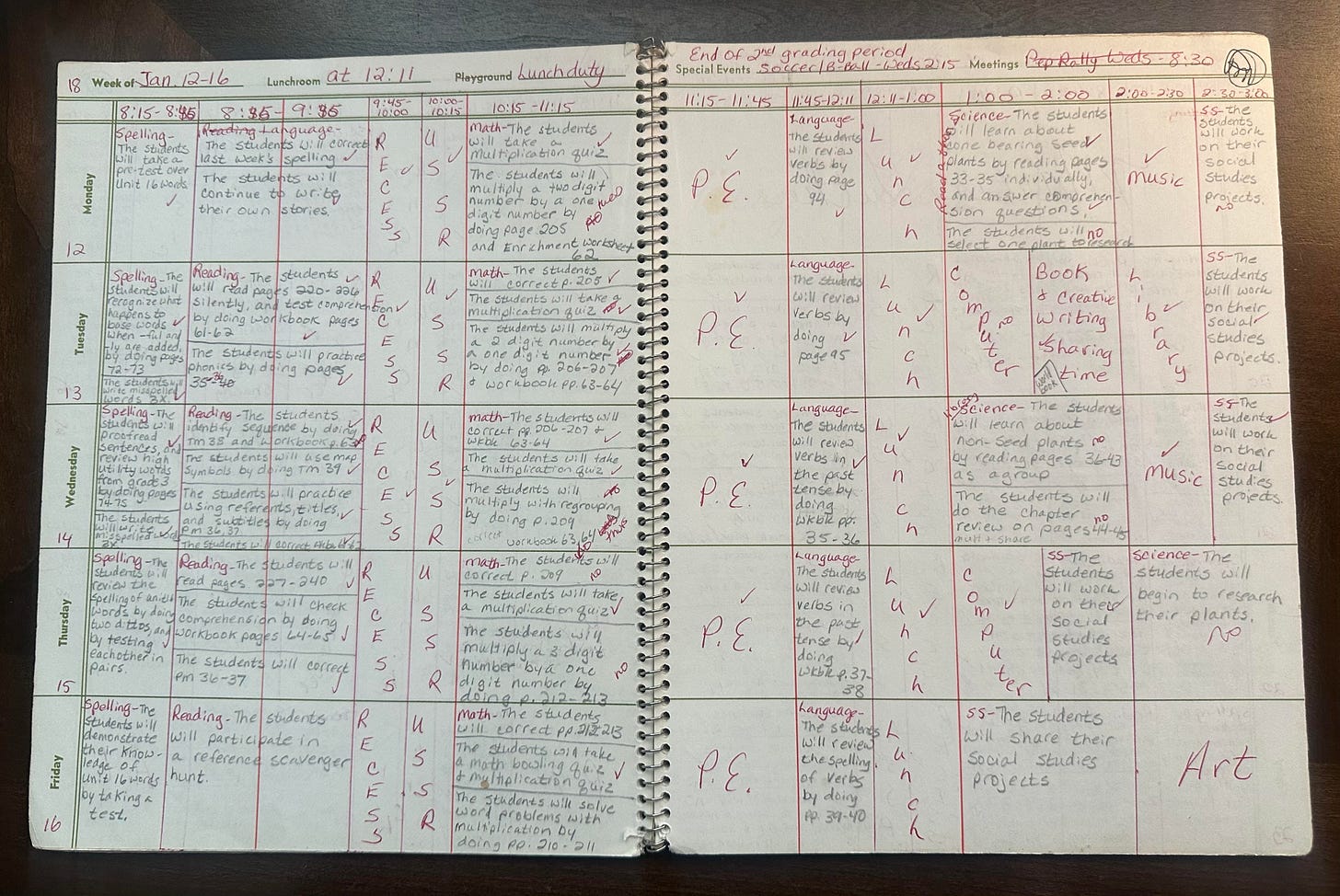

Robbins does an excellent job of demonstrating how the expectations and responsibilities placed on teachers ramped up significantly over the last 40 years, beginning with the 1983 publication of the Department of Education Report A Nation at Risk. This report came out just before I started teaching, and I have seen firsthand how the job of teaching has changed from manageable to mammoth, from being respected to reviled. Robbins cites 2002’s No Child Left Behind, Obama-era Race to the Top, and the Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015 as stops along the way to a profession that many now find untenable.

In the book, teachers Penny and Rebecca both wondered if perfectionism was at the root of their burnout and as such blamed themselves for their job dissatisfaction. This is where it gets tricky. There actually are interventions that can not only help teachers battle perfectionism, but they can shore up their mental health in a variety of ways: dealing more effectively with conflict, avoiding cognitive distortions, setting boundaries, showing self-compassion, avoiding people pleasing, practicing mindfulness, and more. But, without a supportive school environment, those interventions will only go so far. Survival mode is not conducive to self-actualization.

Perhaps the author’s words in the Prologue sum up well a main take-away from this important book:

“‘Other countries treat teachers like doctors and lawyers: true experts of their subject and craft,” a Pennsylvania AP English teacher said. ‘In the U.S, they say things like “Those who can’t, teach.” After the teachers in this book escort you through their year-in-the-life stories, our hope is that you’ll never tolerate that message, or anything like it, again.” (p.4)