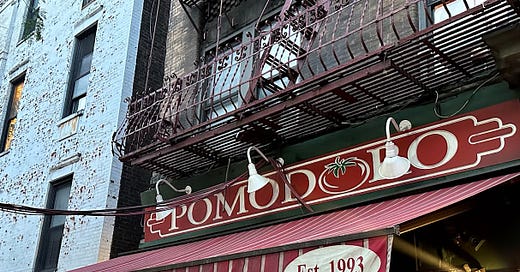

Last month, my husband Sean and I enjoyed a lovely Italian meal at Pomodoro in Manhattan, famous to some as the spot where Kramer broke up with George on Seinfeld. Minutes after we were seated at our table, the server ushered an older, single woman to the table next to us. Typical of New York restaurants, the tables are crammed together such that it feels like one is on a big group date.

And yet, my husband and I would have noticed the woman anyway, even if she wasn’t the width of a pizza slice away from us. Over the last few days, we were intrigued by the number of elderly women we saw walking alone around the Upper West Side. This by itself is not remarkable, but when cast next to the grittier characters of the city, these women were notable in the way they seemed to own the streets. Their eyes did not dart side-to-side as they roamed. They strode confidently, despite many of them having movement limitations.

I wonder about the lives of these women, especially as I chase them in age. Did they always live here? What keeps them living in a place that, with its uneven sidewalks and bitter cold winters, is seemingly trying to boot them out? Do they feel the same fear I sometimes do as a woman walking the NY streets alone? (I think I know the answer to that last question.)

Although my Sean is famous for chatting up strangers, he did not strike up chitchat with this particular woman. He is, however, a trained observer, and he noticed the woman jokingly ask the waiter if he had a blanket for her tiny frame because she was cold. She devoured a three-course meal that would put both of us under. She had a copy of the Wall Street Journal tucked into her tote bag.

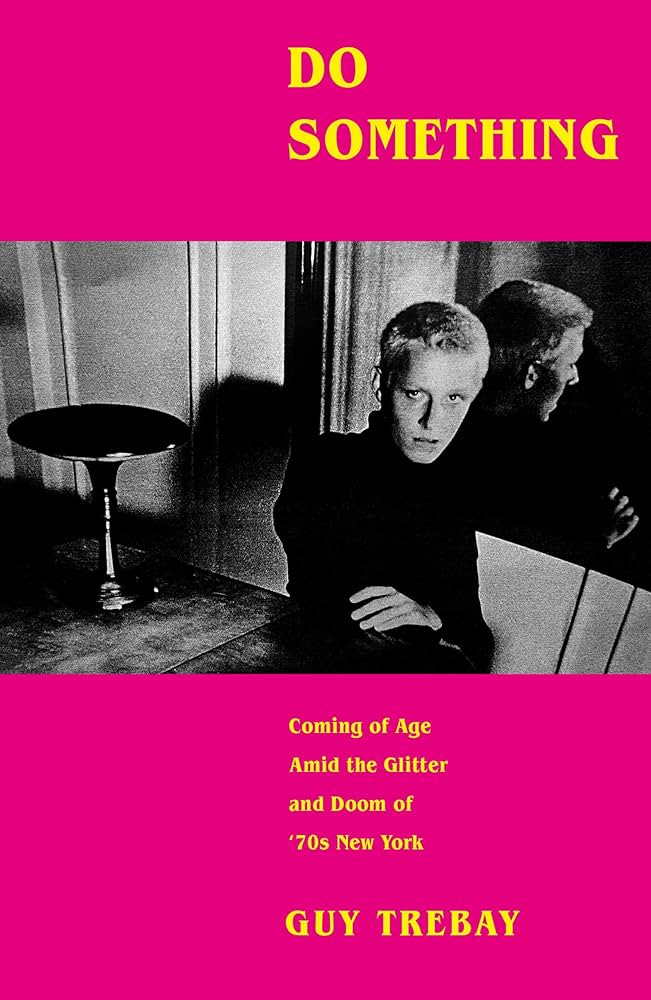

But Sean missed something that I noticed as we paid our bill and left. In the corner of her table was placed the book Do Something: Coming of Age in the Glitter and Doom of 70’s New York by Guy Trebay.

I never heard of this book, never heard of Guy Trebay. But I felt a strong urge to pick it up and read it. Yes, I have 100 books on my to-read bookshelf at home, but really what’s one more? I was so curious to know about this book the woman brought along as her dining companion.

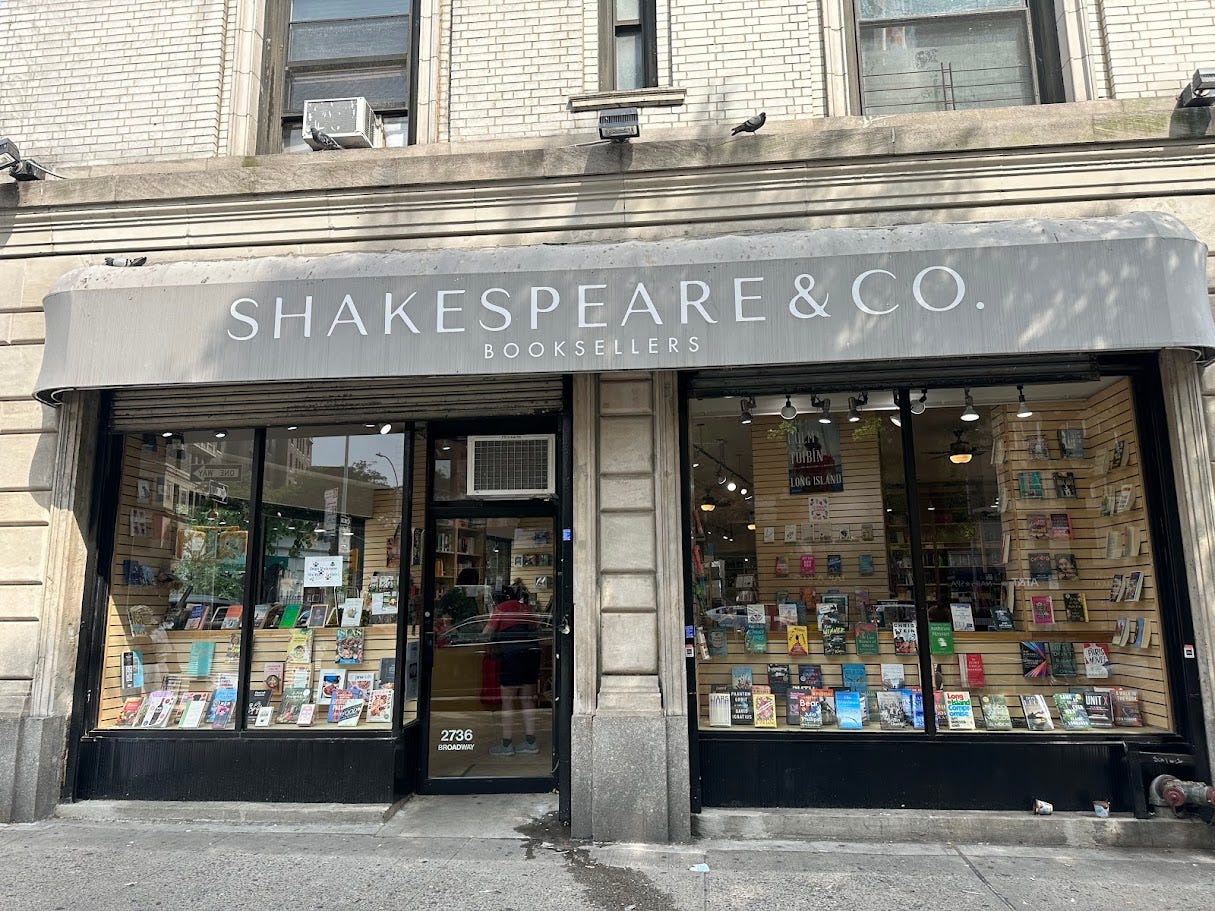

The next day, I found my way to Shakespeare & Co Booksellers on 105th and Broadway and located the book featured amongst new titles. After reading the book’s subtitle as I held it in my hand, the mystery of the woman’s life story burned in me. By my estimation, the woman would have been in her mid-20s in the “Glitter and Doom of 70s New York.” Did she live here? What did she see? What stories are locked beneath her now elegant exterior and unexpected ability to eat a volumes of pasta?

I won’t get to know any more about that woman, but I now know a lot more about Guy Trebay after reading his well-crafted memoir. Trebay is a style writer for the New York Times and has written for a host of publications including the New Yorker, the Village Voice, and Esquire. And reading his book transported me to a place and time so very different from my own upbringing, but one in which I’ve always been fascinated.

Trebay chronicles his movement from a middle class early childhood in the Bronx to a new-money life growing up on Long Island. But the bulk of his story transpires during the early to mid-70s in the art and culture scene of Manhattan. Trebay introduces the reader to a host of artists, drag queens, dreamers, and assorted Warhol Factory figures who embodied the scene at a very colorful time in the city’s history.

I Googled every character mentioned in the book, which was essential for this girl raised a decade after Trebay in the suburby bubble of Scottsdale. This required dropping the book often to go down deep Wikipedia holes. But I spent even more time looking up various words Trebay uses, such as vedette and plinth and lintel. I complete the New York Times crossword puzzle every day, but I learned more words reading this book than I have in a long time, and that was very gratifying for me.

Trebay’s family history is complicated, and one result is the wild weeds sort of childhood he experienced. Out of parental neglect came the opportunity to experiment, take risks, fall down, get up again. He was, what my husband terms, a “free child.” And it is through this liberation that Trebay flung himself into adulthood with a great deal of openness to experience and eventually forged a career as a writer.

I contrast Trebay’s upbringing with my own, in which my parents took more of a hothouse garden approach. I only dreamt of moving to the Big Apple as an 18 year old dancer, and I sometimes wonder what might have been if I had taken that leap. But Trebay’s book transported me to that place and time in history and culture, at least for a moment.

The woman sitting next to us in Pomodoro might just as well have been from Akron who picked up the book to learn more about this city she is visiting with her bridge club. (A woman with stories of her own, to be sure.) But maybe she was really Mary Woronov, reminiscing on her years as a cult star in Andy Warhol’s Factory and recalling a life and time that only precious few knew firsthand. I know better than to underestimate the life of any older woman.